Workers ought not to be exclusively absorbed in these unavoidable guerilla fights incessantly springing up from the never ceasing encroachments of capital or changes of the market. They ought to understand that, with all the miseries it imposes upon them, the present system simultaneously engenders the material conditions and the social forms necessary for an economical reconstruction of society. Instead of the conservative motto, ‘A fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work!’ they ought to inscribe on their banner the revolutionary watchword, ‘Abolition of the wages system!’

Karl Marx, Value, Price, & Profit.

Between the 1950s and the early 1970s, much of the global periphery entered what appeared to be a decisive historical window. Manufacturing output in several late-industrializing economies grew at annual rates exceeding 7%. Public investment routinely crossed 25% of GDP. State-owned firms dominated steel, energy, transport, and telecommunications. Tariff walls averaged above 40%, capital controls were tight, and labor absorption, while uneven, moved in the right direction. Rural populations were displaced, but they were displaced into factories, ports, and construction sites rather than into permanent surplus. Against the boomer (including boomer-adjacent gen X) nostalgia, this was far from a golden age, though it may have been at some point within the social caste, but it was a coherent one. The state had a clear function: to force capital accumulation where it would not spontaneously occur, and to subordinate competing class interests to the nation-building project.

Rather than all at once, that coherence collapsed in stages. By the late 1970s, profit rates declined, import substitution hit technological ceilings, and external financing replaced internal surplus as the main driver of investment. Debt rose several times faster than output. Manufacturing employment plateaued, then fell, even as output figures continued to climb. Neoliberal structural adjustment inaugurated the model’s total exhaustion. When trade was liberalized and finance opened, it became clear that national accumulation had been overtaken by a global system organized around monopolized technology, concentrated capital, and mobile value chains, in accordance to the Washington Consensus. It was a rupture from the old forms of capital accumulation, and it meant a rupture from the old ways of class struggle in both camps of the world-bourgeoisie and the international proletariat. The state survived this rupture, but in irreversibly altered form. Its coercive, exploitative, managerial instruments remained, yet with their formal purpose shifted from building productive capacity to managing the constraints it encountered in the global market, in the birth pangs of integration and restructurations. Herein unfolds the sharpening intra-class struggle between the two domineering fractions of capital: the nationalists, and the globalists.

The present inherits this outcome without acknowledging it. Industrial policy retains relevance only in the forms of subsidy, tax incentive, or infrastructure for circulation. Growth resumes on paper while employment stagnates. Ports expand faster than factories. Logistics outpaces production. Credit replaces wages as the means of social reproduction. What looks like real development is instead an emptied rehearsal for a stage which seemingly disappeared out of nowhere. The modern state can only plan adjustment; it intervenes today only to stabilize conditions it no longer controls.

This is the political atmosphere of the periphery today where the state presides over the modernization of mal-development. The developmental state depended on an expandable world market, relatively low technological barriers, and the possibility of absorbing labor into national circuits of accumulation. In the Philippines, manufacturing output has since the ‘70s grown intermittently, its share of employment steadily plateauing. Infrastructure spending has surged, primarily in transport, energy, and logistics, not in productive (ie., self-sustainable) development. Export zones multiply while domestic supply chains thin. Growth figures in cloud spreadsheets coexist with chronic underemployment, mass migration, and household indebtedness on the ground. The state remains active and visible, but its activity increasingly mediates between global capital and surplus labor rather than organizing accumulation in its own right. The peripheral capitalist state today operates after history.

False antagonisms

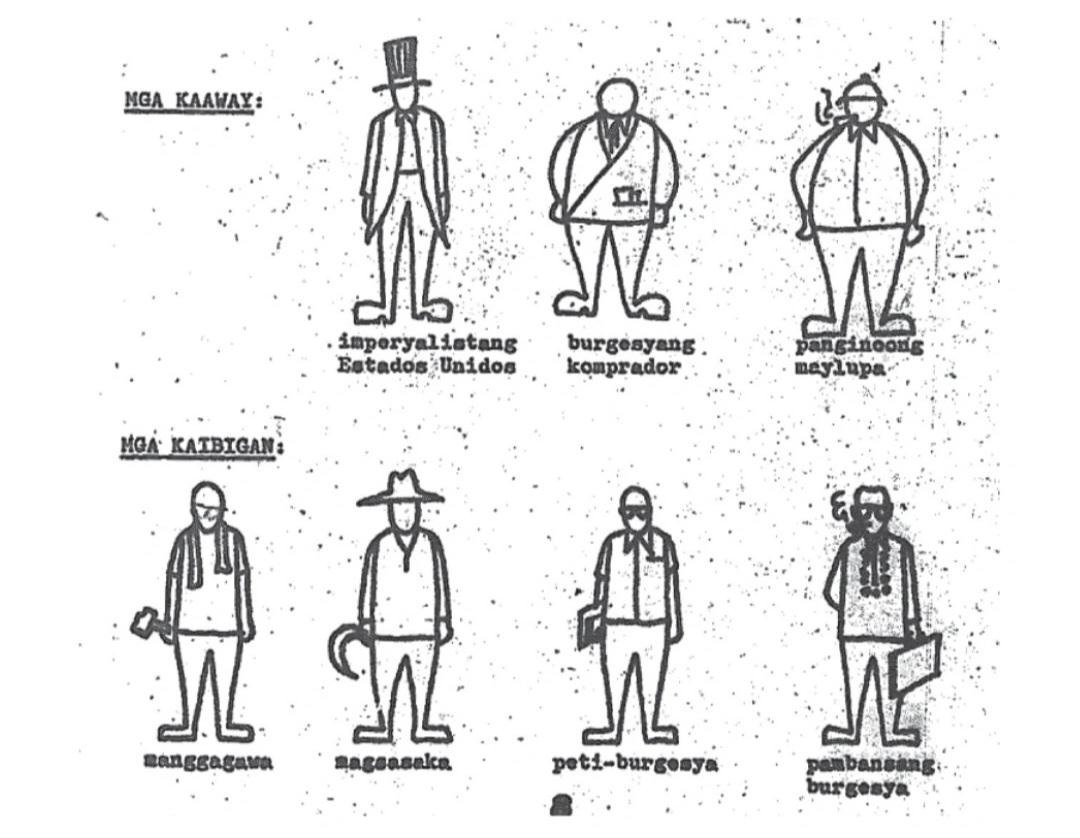

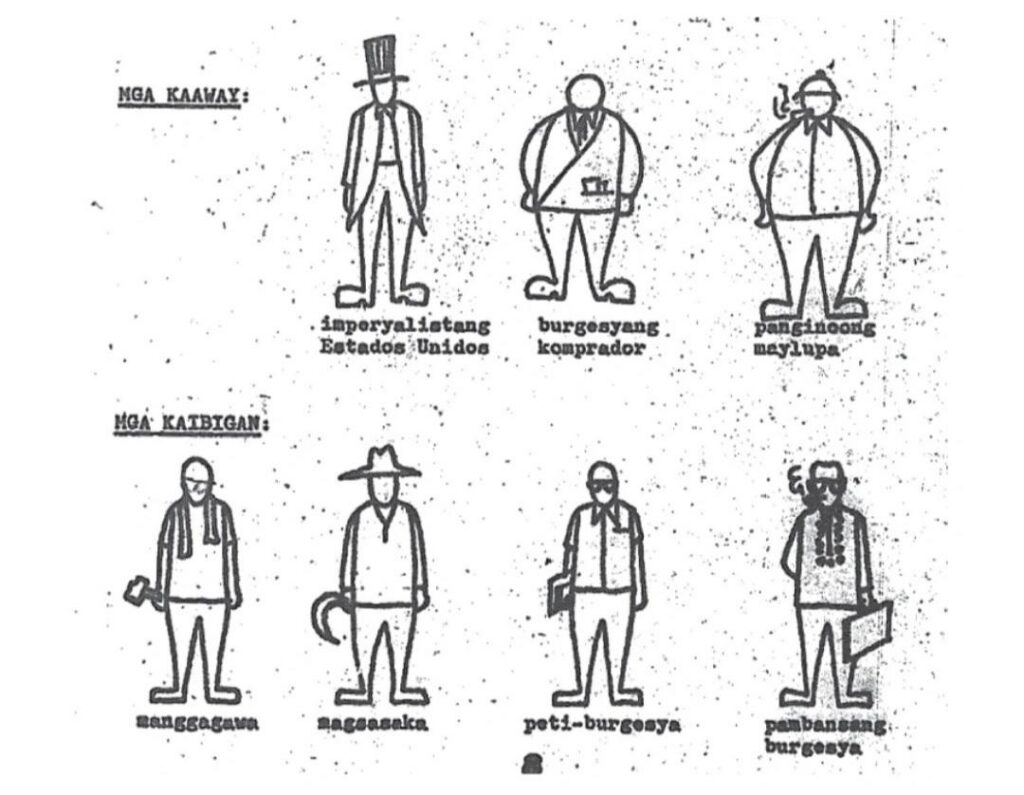

As national accumulation loses coherence, capital fragments into competing fractions whose interests diverge at the level of strategy, scale, and geopolitical-spatial anchoring. In the periphery, this division commonly appears as a conflict between “national” and “transnational” capital. This internal dialectical contradiction structures new norms of bourgeois political life, from electoral competition to much of the left’s strategic horizon derived from an already-derivative political imagination. Insofar as both fractions operate within, and reproduce, the same post-developmental constraints of imperialism, we have no more than a false antagonism—false, precisely because this doesn’t sublate the antagonism between the bourgeois and the proletarians. On the contrary, the exhaustion of developmentalism has only sharpened it, at the same time as it sharpens the competition within the respective classes themselves. The conflict between these two fractions of capital concerns how to manage their respective integrations into world-imperialism, whose friction is the permanent tendency to re-divide the earth and the spoils of crisis.

CPP’s Drowing: Tulong sa Pagtuturo; pulled from Joseph Scalice’s article, “55 years since the founding of Kabataang Makabayan (KM)”.

National capital in the periphery is no longer what it was during the classical developmental (ie., “Fordist”) period. No longer is there an emergent industrial bourgeoisie struggling, that is, actively intervening, to consolidate domestic production against emerging foreign competition. It is now a heterogeneous, only semi-coherent bloc of construction firms, real estate developers, logistics operators, agribusiness interests, utilities, retail conglomerates, and politically-connected rentiers (landlord-capitalists, compradores). Its accumulation strategies are territorially fixed but structurally dependent. Profitability derives from state contracts, land conversion, naked corruption, monopoly concessions, and access to credit, rather than from sustained industrial development. This fraction requires the state only insofar as the monopolized-hence-totalizing violence at its behest continues to be a guarantor of rents, regulator of political access, and disciplinarian of labor, whether through state and yellow unions or through direct violence.

Transnational capital, by contrast, is characterized less by all the baggage that comes with national identity (including its peripheral role, say, in the Philippine case, as a “service economy”, or reservoir of cheap migrant labor) than by function. It operates through transnational value-chains, monopolized technologies, and financial mobility. Investment decisions made by this fraction are driven by cost-differentials, logistic efficiency, and risk management in lieu of long-term commitments to national development or, more appropriately, short-term rent-seeking through patronage networking and dynastic turf-building. In the periphery, transnational capital enters primarily through export-oriented manufacturing, which entails the development of extractive industries, infrastructure finance, and services (accessory to circulation). Its demands on the state are selective but consequently (unconscious or otherwise) potently subsumptive: stable macroeconomic policy, flexible labor markets, legal safeguards, and infrastructural connectivity, all of which become anchor-points for domestic capitalist development (ie., integration). It has little interest in national industrial development beyond what is immediately profitable, though competition may at times compel it to invest more than it would have preferred to in order to gain an advantage and guarantee returns.

In the Philippines, large domestic conglomerates like Ramon Ang’s San Miguel Corporation dominate construction, energy, transport, and real estate. Their profitability is tightly linked to public infrastructure programs, land re-zoning, and regulatory privilege. At the same time, export-oriented manufacturing, business process outsourcing (BPO), and logistics depend on foreign direct investment, trade liberalization, and integration into global accumulation networks. State policy can only alternate between courting foreign capital and appeasing domestic elites to ensure they get their piece. Infrastructure spending expands primarily to facilitate circulation (and line bureaucrat pockets) rather than to develop domestic productive capabilities.

Domestically, one of non-industrial development’s pillars is the marked resilience of the landed bourgeoisie. Unlike in South Korea and Taiwan, where US-backed land reforms in the 1950s dismantled the landed bourgeoisie as a political force, freeing capital, cultivating a domestic market, and removing a reactionary bloc to state-led industrialization, the Filipino landed bourgeoisie successfully neutered every reform effort since the granting of the country’s nominal independence from the US in 1946. They seamlessly translated agrarian monopoly into commercial, financial, and later industrial capital, creating an oligarchy whose wealth derived from political rent, monopoly control of domestic markets, and comprador partnerships, in lieu of productive export competition. The Philippine state never achieved the autonomy of South Korea’s Economic Planning Board; it has remained, and today remains, a captured apparatus for middle-manning oligarchic and crony competition. Industrial policy, where it existed, served as a tool for dispensing protected rents to favored factions which only cemented a consumption-oriented Import-Substitution Industrialization (ISI) model, in contrast to the Newly-Industrializing Countries’ (NICs) export-oriented ISI.

Externally, the Philippines lacked the geopolitical weight that granted the NICs their critical edge. South Korea and Taiwan operated under a US security umbrella that provided not only aid but also unparalleled market access and tolerance for the very protectionist and subsidy policies now prohibited under WTO rules. This permitted a decades-long period of “infant industry” protection simultaneously forcing discipline through export targets. The Philippines, while a treaty ally, was never the recipient of such concerted, strategically motivated industrial nation-building, instead predetermined to become by then a source of raw materials for external industrial processing and manufacture. By the time it might have attempted a belated developmental push, the global institutional environment had since ossified and settled. Binding commitments to the WTO, ASEAN trade pacts, and bilateral agreements locked in liberalization, prohibiting subsidy programs, local content requirements, and strict capital control systems that defined the NICs’ protectionist, export-oriented industrialization model.

Thus when the current global system of monopolized technology and fragmented value chains fully emerged, the Philippines was uniquely predisposed to integration as a dependent node. Its manufacturing sector, historically nurtured for the domestic market, could not compete in high-value exports, thoroughly crushed by the opening up of the domestic market to foreign investors and competition, whose wares had much higher quality for cheaper prices for consumers. The oligarchic economy adapted by specializing in rents from logistics, real estate, mining, and low-value assembly within global value chains tasked with semi-processing electronic assembly and producing automotive parts, aside from raw material extraction. The state’s function adapted accordingly; its “industrial policy” narrowed to providing tax incentives and building infrastructure for circulation (ports, highways, power-grids) to facilitate this integrative role. Catching up in steel, ships, and basic electronics in the 1970s was difficult but, with the greatest global superpower in history backing your development for its imperialist business interests, feasible through reverse-engineering, incremental innovation, and near-unlimited investment capital. Today, breaking into monopolized sectors like semiconductors, aerospace, or pharmaceuticals requires R&D investments and scale that are orders of magnitude greater, protected by intense intellectual property regimes (see: TRIPS Agreement). Any residual nationalist impulse is structurally checked by the impersonal disciplinary power of hyper-mobile finance capital; capital controls or directed credit would trigger immediate capital flight and credit score downgrades from agencies like Moody’s and S&P.

The “political will” necessary for developmentalism would require the native bourgeoisie to will its own transformation from a myopic rentier-comprador class into a risk-taking industrial bourgeoisie, while simultaneously defying the hard constraints of a fully-globalized capitalism. Their wealth derives from rents (land, real estate, monopolies in utilities, mining concessions, retail), political patronage (state contracts, protected sectors, dynastic lineages and bulwarks), and comprador activities (importation, franchising, representing foreign brands). Industrial deepening is risky and offers lower returns than rent-seeking in the short-term, with no guarantee of eventual profit in the long-term due to overwhelming competition. Their interests are aligned with liberalization (to access cheaper imports for their businesses) and, ultimately, financialization. Perhaps this is indeed a lack of will, but it is also, in the first instance, conditional of the shaping of this will, a structural impossibility. While the state appears to stand atop society, piloting it from the cockpit, it is nothing more than the condensation of a totalizing social formation oriented towards chronic dependency.

The conflict between these fractions is of course real, and a source of much of the crises being suffered through by proletarians (semi-proletarians included) in the peripheries, but it is ultimately bounded by the hard constraints of the imperialist world-system. National capital seeks protection, subsidy, and preferential access where transnational capital seeks liberalization, deregulation, and maximum capital mobility; both require the state; both rely on surplus-labor and the violent consequence of inter-class competition among proletarians; both operate within a global system that constantly delimits their strategic horizons. The state becomes the terrain on which this conflict is mediated, where these manifolds of determinations converge and find resolution (or, attempts at such). Policy oscillates between nationalist rhetoric and globalist accommodation, between promises of sovereignty and commitments to competitiveness and bilateral trade agreements. These oscillations are often interpreted as ideological incoherence or political opportunism when, in fact, they reflect the structural impossibility of reconciling developmental aspirations with the contemporary organization of capital as a planetary “substance” of social life. What tends to happen is the hollowing-out of whatever is left of national-developmentalist aspirations of the native bourgeoisie, reduced to what is effectively political veneer, as the inevitable march of the Juggernaut that is capital’s transnationalization, in its historical quest of alienated homogeneification, crushes and subsumes local production processes from the inside and crushed under its weight.

This configuration produces a specific form of brutality: workers are disciplined in the name of competitiveness without being integrated into stable industrial employment; infrastructure projects displace communities while creating limited long-term jobs; export zones offer employment under conditions of precarity; national capital extracts rent while deflecting responsibility for the deficit in social reproduction onto semi-proletarian households, OFW migrants, and informal economy networks. All the while, transnational capital secures its surplus while externalizing risk to the peripheral state, who mediate these processes through absorbing political blame, ultimately powerless, in the name of the law of value, to overturn the underlying logic of the world.

Conserving what’s lost

Reactionary movements arise from the disjunction born of post-war developmentalist capitalism, for both the core and periphery/semi-peripheries alike, depending on one’s determinate position within the world-system. They respond to declining job security, wage stagnation, housing precarity, eroded welfare, and increased market volatility. These conditions are experienced as loss of stability and a future of class mobility for the working and middle classes. In the core specifically, because global capitalism cannot be confronted through national political mechanisms, this apparent “decline of Western civilization” is interpreted as betrayal and conspiracy by elites, outsiders, or cultural enemies; here, declining industrial employment collides with residual welfare capacity and imperial rents, which seems to produce a defensive (ie., “right-wing”) nationalism oriented toward restoration of some past privilege or historical glory. In the semi-periphery, export-dependence and wage suppression, intersecting with integrationist projects (eg., European Union) which are perceived as threats to national identity, generate authoritarian stabilization projects that promise order and compensation through identitarianism with little material redistribution. In the periphery, where welfare and employment never stabilized social reproduction, political reaction more often takes the form of left-nationalist or moral anti-imperialism motivated by subsistence struggles. Reactionary politics reorganizes consent under conditions where no national (ie., traditional, known, immediate) solution to material decline exists.

In the United States, The MAGA movement, also increasingly apt as Trumpism, developed out of decades of deindustrialization, union defeat, and labor-market fragmentation. From the 1970s onward, manufacturing employment declined while production was reorganized through offshoring and automation. Wages stagnated while productivity levels and profit-rates shot up to the sky. Social reproduction increasingly relied on credit and what little welfare, bureaucratic as it is, existed. The promise that globalization would compensate for these losses ultimately failed to materialize in the quality of life of the working class. MAGA, or Trumpism, frames this experience as the outcome of unfair trade, immigration (legal or illegal), and conspiring cabals of liberal elites. Its policy proposals of imposing absurd tariffs, border enforcement and internal purging of immigrants, and quasi-protectionism, are all attempts to roll back the present to the collapsed horizon of post-war, pre-neoliberal accumulation. Trump dresses himself as presenting the American working class what Reagan has denied them in the neoliberal turn: an “alternative” to globalization, to neoliberalism, to imperialism, to sickness, starvation, and death. Merely that, as time passes, Reagan has only been vindicated, at the cost of our class’ suffering, and Trump has only been revealed as the thoroughly bourgeois opportunist politico-businessman he has been all this time. To call him a prophet of neoliberalism would be improper, since in reality he only declared what was already by then a truth of the capitalist world: “There is,” truly, “no alternative.”

Similar dynamics appear in Europe in different institutional forms. The rise of the AfD (Alternative für Deutschland) in Germany for one is inseparable from an export-led growth model based on wage suppression and labor market dualism it adopted in 1990. The Hartz reforms stabilized German competitiveness in the world-market by shifting adjustment costs onto workers and peripheral European economies. Aggregate growth reflected in corporate profit-rates across the board coexisted with precarity and declining public welfare; the AfD effectively channels consequent discontent toward the European Union, migration, and multicultural liberalism, the party itself remaining largely neoliberal, openly in support of deregulation and state non-intervention, in its economic positions. In France, Italy, and other parts of Southern Europe, reactionary movements draw support from regions affected by deindustrialization, austerity, and long-term unemployment. In Eastern Europe, Rightist regimes (eg., Fidesz–KDNP Hungary, PiS Poland) consolidate power within economies integrated as semi-peripheral manufacturing zones. Growth occurs through foreign investment, low wages, and limited technological upgrading. Living standards lag behind core economies, emigration drains labor markets, demographic reproduction weakens. These nationalisms attempt to compensate for economic dependency by asserting cultural sovereignty and political control.

In Indonesia, post-Suharto democratization coincided with the deepening of market liberalization and decentralization. Accumulation is, not unlike much of Southeast Asia, structured through extractive industries, logistics, and low-wage manufacturing tied to global value chains. Among the results we observe today are regional inequality, labor precarity, land dispossession, and youth underemployment. Street riots and episodic mass protest-mobilizations are time and again incapable of articulating a coherent alternative project and instead function as release-valves for social pressure, relapsing onto bourgeois forms of political mediation and resolution. In Bangladesh, garment-sector uprisings, joint worker-student revolts, and urban unrest arise from extreme export dependence, hyper-exploitation of labor, and the collapse of rural reproduction. In the face of wage stagnation and union suppression amidst recurring industrial disasters, growth rates remain nominally high. Insurrection here targets immediate conditions of survival. Unlike in the imperial metropolises and semi-peripheries where protectionist, identitarian ideology and Volkisch consciousness are the dominant media of obfuscation and confusion against class struggle, here, in the peripheries, the material limit of subsistence struggles act as the basis and multiplier of left-wing nationalist “anti-imperialist” ideology to serve the same purpose.

Duterte’s administration in the Philippines expanded infrastructure spending, deregulated foreign investment, protected export enclaves, and preserved labor flexibilization. The drug war and militarization functioned as instruments of social discipline in a context where stable employment was never a guarantee nor a norm and welfare was pork barrel. Populist violence in the war on drugs and against activist civil-society was the Spectacular cover for his administration’s discovered failure to overcome structural constraints and facilitate real development. Against his performative hostility to the US and flirtations with China, the Philippine economy remained just as embedded in transnational circuits of capital, logistics, finance, and labor export—circuits which tie the Philippines inevitably to the US by a thousand chains. Manufacturing continued to stagnate in employment terms; growth remained dependent on remittances, real estate, construction, import-dependent consumption, and export-oriented services. Infrastructure projects under “Build, Build, Build” were mere accessories to circulation and chronic (inter-)dependency (importation, exportation). Meanwhile, Marcos Jr.’s pivot-back to Washington, reaffirmation of trade liberalization, courting of foreign direct investment, and the emphasis on macroeconomic stability is the normalization of the same trajectory behind a “calmer”, more investor-friendly facade. In this situation we might say Duterte represents nationalist capital while Marcos represents globalist capital, both fundamentally deadlocked on the same world-integrating trajectory underneath their superficial ideologies and proverbial boxing matches in the national government and International Criminal Court.

Limit-points of praxis

To much of our dismay, the crisis of development does not automatically generate a mass revolutionary politics. It encourages, instead, for an interim period, the persistence of political forms whose material underpinnings have already been eroded by the unceasing, indiscriminate march of capitalist “progress”. These forms retain relevance at the level of ideology and organizational habit, but, owing to a blindness to path-dependency, they operate within a historical terrain that no longer corresponds to their professed strategic goals. We must locate the precise points at which their internal logic encounters the objective limits of global capitalism.

Nationalist Developmentalism: Classical developmental strategies presuppose (and, for a time, really encountered) a state capable of acting as a centralized organizer of accumulation. This capacity rested on three determinations: (1) partial insulation from global capital flows, (2) an ability to discipline domestic capital fractions, and (3) the expansion of productive sectors, preferably industrial-manufactory, capable of absorbing the excesses of proletarianization in the countryside. In today’s periphery, not one of these remains. Capital mobility constrains fiscal, monetary, and industrial policy; domestic capital increasingly derives profitability from state-mediated rents, logistics, and speculative activity rather than productive reinvestment; labor absorption is structurally blocked by technological monopolization and the fragmentation of production at the world-scale. Political strategies that treat the state as a lever for national development misidentify its actual role within global value relations. The conditions we encounter today only confirm to us that capitalism is not a social phenomena enclosed (or truly encloseable) within a coherent nation-space.

This defines the structural limit of nationalist praxis, in presupposing that political sovereignty can be converted into economic autonomy. Under present conditions, that is, of “neo-colonialism”, “semi-colonialism”, “dependency”, “peripherality”—what have you—sovereignty is mere shiny-white veneer for decomposing teeth; peripheral states retain discretion over taxation, repression, infrastructure-siting, and regulatory enforcement, but these capacities operate within a field already subsumed and determined by transnational capital. Protectionism has run its course; liberalization only deepens not just dependence (one-way relationship), but interdependence. Nationalism can only persist as a specifically reactionary political form in the 21st century precisely because its economic content has long since been hollowed-out. The considerations on the immense task of class conciliation, on the question of political will, to prioritize nation-building can only take the form of a Corporatist state which pegs down the landed bourgeoisie, cultivates the industrial bourgeoisie, prioritizes the welfare of the middle-classes, and violently subordinates the labor movement, rural and urban, to the interests of the collective “producers” of the nation. We are, to say the least, not interested in the economic models of Fascism, of National Syndicalism, of National Socialism, even when the masses look to Lee Kuan Yew’s Singapore, Marxist–Leninists look to the Jucheist DPRKorea, among other “actually-existing” Socialisms, and Social Democrats look to China as ideal-types.

Social–Democratic strategies: Social–democratic and populist strategies assume that reforms can accumulate over time and gradually strengthen the material power of the working class. This assumption was predicated on a historical situation in which productivity growth, employment expansion, and welfare reinforced one another. That situation no longer exists. Today, reforms operate within tight structural limits as a zero-sum game where wage gains are offset by precarious work, subcontracting, and household debt; social welfare programs rely on regressive taxation or borrowing and hence reproduce fiscal vulnerability in lieu of stabilizing social reproduction; participation in democratic institutions integrates organizations into state management without expanding their independent capacity to confront and interrupt capital accumulation as such. Social–democratic reformism presupposes that these conditions persist in attenuated form and can be reactivated through redistribution, institutional inclusion, or policy correction.

Counter-hegemony: Counter-hegemony, as famously theorized most systematically by Gramsci, later generalized across the Left, begins from the premise that capitalist domination is primarily stabilized through civil society; culture, ideology, institutions, norms, and consent. Power is exercised less through direct coercion than through the organization of meaning and everyday-life. From this follows a strategic orientation in which the revolutionary task is to construct an alternative hegemonic bloc within existing society prior to rupture. The party of counter-hegemony, posited as an independent revolutionary subject external to or insulated from bourgeois society, treats capitalism as a malleable social order whose contradictions can be neutralized or displaced through cultural struggle, rather than as a totalizing mode of production governed by invariant laws. Counter-hegemony assumes that civil society can be occupied independently of the capitalist relations that structure it—in this insight we glean that Gramscian counter-hegemony operates on the same theoretico-practical register as Social Democracy.

In reality, the party is an autoreflexive organism which identifies its origin point from the dynamics of class struggle under bourgeois society itself, and becomes class struggle’s function, in full awareness that those pressures will act on it continuously. This is why it necessarily minimizes sociological embeddedness, cultural work, and alliance-building a la bourgeois political party-building. The more the party embeds itself in civil society, the more it is compelled to speak its language. From the structural lens, counter-hegemonic projects reproduce themselves through recognition, funding, and procedural legitimacy rather than through disruption of accumulation. They assume a more-or-less workable continuity of counter-hegemonic power-building along a stable axis of temporality while capitalism in the periphery is governed by abrupt shocks, crises, and permanent geopolitical uncertainties. This means that when political openings appear, they do so suddenly and close quickly.

In geopolitical terms, counter-hegemony in the current order means multilateralism. Multipolar or “counter-hegemonic” strategies that oppose US unipolarity through BRICS alignment or China-led “socialist multilateralism” identify imperialism as a geopolitical configuration composed of competing, semi-independent national economies that create an emergent “world-capitalism” in interdependence, rather than as the specific form of capitalism at the world-scale. US dominance is posited as the invariable cause of underdevelopment instead of simply being its historically-contingent organizer. Replacing a unipolar order with a multipolar one reorganizes competitive discipline over the same world-market, governed by monopolized technology, financialized accumulation, and integrated value-chains. Peripheral states remain structurally compelled to attract capital, suppress labor costs, and specialize in low-value segments of production. There is nothing special about, say, Chinese capital that can suspend these imperatives.

Multipolarity can only intensify inter-imperialist competition while narrowing room for maneuver as peripheral states are locked into overlapping dependencies. By framing development as alignment against a dominant imperial pole, it subordinates working-class interests to state and capital strategies in the moral language of anti-imperialism. Labor discipline, repression, and austerity are justified as necessary for positioning within a hostile global order. Class struggle is displaced upward into diplomacy and industrial policy while exploitation intensifies at the point of production.

Finally, each of these forms of praxis attempts to resolve capitalist contradictions through mediations that presuppose the continued reproduction of capitalist social relations. Nationalism seeks to re-territorialize accumulation where reformism (whether Social–democratic or Gramscian) seeks to plaster into it a friendly, human smile. Both operate by narrowing the field of political imagination to what can be administered by the state, displacing conflict away from the relations of production and reproduction that generate crisis. When these strategies inevitably fail, the resulting disillusionment has historically weakened class autonomy and opened space for retaliatory, violent counterrevolution. In either case, capitalism is treated as a system whose limits can be negotiated rather than abolished whether explicit or otherwise to their proponents. The historical trajectory of the periphery since the 1970s indicates that these negotiations now occur entirely within the permanent management of permanent crisis.

Remarks

The working class in the periphery is no longer unified by stable industrial employment or national circuits of accumulation. Its passive condition as variable capital is that of a “unity-in-separation”, fragmented across formal and informal sectors, production and circulation, domestic and migrant labor, nationalities and cultures, regions and religions. Organizational forms developed within earlier terrains of class struggle are incapable of unifying the segmented class because their mediations which presupposed stable points of leverage simply no longer exist. At the same time, the hollowing-out of developmental accumulation generates a contradictory opening. As the state loses its capacity to integrate labor, its legitimacy consequently erodes. And as accumulation fails to absorb surplus populations, struggles increasingly target immediate conditions of reproduction. These struggles tend to be localized, episodic, and oriented toward survival rather than reform. They do not, in themselves, constitute a revolutionary movement but do, however, indicate a shift in the locus of antagonism, away from mediated demands and toward direct confrontation with the political conditions imposed by capital.

For a communist critique, the task is, as it has always been, to expose world-capitalism’s limit-points. If national accumulation can no longer integrate labor, the terrain of struggle shifts accordingly. Conflict concentrates around social reproduction, circulation, subaltern surplus populations, and state violence rather than wages and industrial policy alone. Housing, transport, food, energy, debt, migration, and policing become central sites of antagonism. These struggles are fragmented and episodic, but they are not marginal. They reflect the real points where capitalist reproduction now encounters a steady resurgence of class resistance.

The antagonism between nationalist and globalist capital delineates the field within which crisis, one of which being that of “development”, is managed; the state bears the scars of preceding proletarian struggles; and recognizing this is a precondition for breaking with strategies that seek salvation in national accumulation. We must, therefore, confront that which renders the state incapable of transformation.

Relevant references

- John Smith, ‘Imperialism in the Twenty-First Century’

- Alejandro Lichauco, ‘Nationalist Economics’

- Tables 2.1, 2.2, and 2.3 from: Bénétrix, Agustín S., Kevin Hjortshøj O’Rourke, and Jeffrey Gale Williamson, ‘Measuring the Spread of Modern Manufacturing to the Poor Periphery’. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198753643.003.0002

- Brazil, Taiwan, South Korea, Philippines on World Development Indicators by World Bank. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators

- Philippine Review of Economics. ‘Special Issue on Industrial Policy’. Vol. 61, No. 02, December 2024.

- Hassel, Anke & Di Carlo, Donato. (2025). Germany: Adjustments of an Export-Led Growth Regime.